Lounging in the window seat of her country house circa 1780, 12-year-old Elizabeth is working on her half finished sampler. Made using costly, brightly-coloured silk thread on linen, it is a fashionable scene of a shepherdess and her flock, beneath a verse from the Bible, an alphabet and rows of symmetrical patterns. Elizabeth is pleased with it, as is her governess, who has been employed to teach her the skills deemed suitable for wealthy young woman of the time.

“The human stories that samplers hold are what makes them so appealing”, says Joy Jarrett of sampler specialist Whitney Antiques. “To own the work of girls who were alive as long ago as the time of the Mayflower, to glimpse something of their schooling, their homes or their families’ country estates, holds an irresistible appeal. When occasionally we sense their emotions – unfettered frustration shown in pulled stitches, squashed words or unfinished works, or the affection in a dedication to a governess, parent or sibling – we cannot help but be moved.”

The word “sampler” comes from the Latin word “exemplum”, meaning an example or model to be followed, and the earliest samplers were a source of patterns and stitches, probably used by experts or professionals. Though Egyptian samplers have been found from around the 13th century, the earliest surviving dated European sampler, now at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, was completed in 1598. It was made (as an adult) by a Jane Bostocke and depicts border patterns, family crests, a deer, a lion and a hunting dog.

The needlework was an important element of a woman’s education: taught by tutors of the wealthy to enable girls to manage their households upon marriage, and in charity schools to poorer girls who would need to earn their living. It was also valued as a virtuous accomplishment, demonstrating industry, self-discipline and neatness, and was part of the curriculum in the growing number of private schools for the daughters of the middle classes.

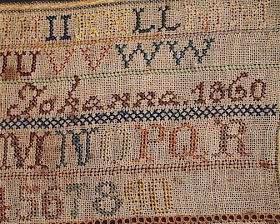

The samplers are of two main types: those with spot motifs, sometimes called “random” samplers,and more common “band” samplers.Random samplers are rarely inscribed, probably because they were for the personal use of professional embroiderers. Band samplers feature patterns and inscriptions stitched in horizontal rows and are often initialled, named and dated.

“Samplers represent a whole history of female education,” says Joy. “A map sampler, for example, was a demonstration of knowledge of geography as well as needlework.” As the century progressed, a greater variety of grounds were used: linen, silk, cotton, wool, tammy (woolen canvas) and tiffany (muslin), stitched with either silk or linen thread.

From the mid of 19th century, samplers suffered an inexorable decline, thanks to the invention of the sewing machines, the availability of cheap manufactured clothing and the reduction in numbers of domestic staff. The introduction of compulsory education in 1870 had an effect, too. “There were books that told teachers how to instruct needlework, so samplers, on the whole, became plainer and less varied,” says Joy Jarrett. “These are generally the school samplers that are most reasonably priced today.”

Expect to pay around £50 – 200 for a simple, mid 19th century schoolgirl sampler, around £1,500 for a Bristol orphanage sampler, and more for a particularly rare, interesting or high-quality examples. The highest price paid for a single sampler at public auction was $465,750 in 2009 for a 1781 sampler by Betsey Bently, daughter of Joshua Bentley, who rowed Paul Revere across the river in his celebrated midnight ride to warn American forces of the approaching British Army.

No comments:

Post a Comment